Compiled by Martin Davis © 2010- 2017

The Ancient Community of Ukrainian Jews

Jews first settled in the Ukraine in the 4th century BC; in the Crimea and among the Greek colonies on the north east coast of the Black Sea. From there they migrated to the valleys of the three major rivers-the Volga River, Don River, and Dnieper River - where it is known that they maintained active economic and diplomatic relations with Persia, Byzantium and the Khazar kaganate. [1].The Early Jewish Community of Kamenets

Kamenets was first mentioned, as a town of the Kievan Rus state, in an Armenian chronicle of 1062 as a town of the Kievan Rus state. In 1241, it was destroyed by the Mongol Tatar invaders. Being an important defensive and commercial site it was gradually rebuilt and in 1352, it was annexed by the Polish King Casimir the Great. Almost immediately it was granted city status with the town and civic rights of the Magdeburg law. which were beneficial to all resident minorities. Jewish people resident in Kamenets would have been granted equalities and freedoms. The first mention of Jews in Kamenets was in the year 1447 when it was recorded that the Mayor of the town prohibited Jews from staying there for more than three days[7]. This use of the application of the banning of Jewish people (De non tolerandis Judaeis) a local historian [8] has concluded that “...the issuing of such a declaration is proof that , despite the ban , Jews not only lived in the city, but even had there own homes and other real estate” within the city walls [8] . Legends also existed about ancient settlements of Jews in the area. For example, a large mound in the town of Felshtin, near Proskurov, was believed to be a mass grave for Jews who died in the Black Death plague of the 1200s. Local peasants believed in the power of the mound and refused to touch it. In 1463, Kamenets became the capital of Podilia voivodeship (region) and the seat of local civil and military administration. The union of Poland (1569) with the Grand Duchy of Lithuania in 1569 again brought the town effectively under the control of Poland. In 1589, city councillors formally accepted the application of citizenship for the city’s Jews and this agreement was confirmed by the Polish King Zygmunt III [8]. However, in 1598, the same king prohibited Jews from settling in the city and suburbs and from engaging in trade there; their visits were again restricted to three days. Whether this applied to resident Jews or to those intending to settle there in the future is unclear. However, from that period there seems to have been a significant Jewish presence in the city and its surrounding districts which continued until the Shoah.Khmelnytsky Uprising and Turkish Rule

The Jewish Community and Fight Against Ghettoisation

After the city's return to Poland in 1699, the some citizens resumed their opposition to Jewish settlement. However, the Jewish community continued to be present within the city and probably in recognition of the importance of the community, the Council of Four Lands met in Kamenets in 1725 [7]. In 1737 the city council submitted a request to the state and church authorities to banish the Jews from the city, maintaining that they had no right to settle there, and were competing with the Christian inhabitants and impoverishing them. King Augustus III expelled the Jews from Kamenets in 1750. Their houses passed to the town council and the synagogue was demolished. The expelled Jews settled in the suburbs (such as the Karvansary district below the fortress which was then an independent township). They also settled in nearby villages, which were under jurisdiction of Polish noblemen, and developed extensive trading activity there which led to additional opposition on the part of the Kamenets complainants. In 1757 a public disputation was held by the in the old town – convened by the local bishop – between the representatives of Podolian Jewry and Jacob Frank and his supporters. After it took place copies of the Talmud was publicly burned in the city on the bishop's orders.Rights of Kamenets Jews Confirmed

Throughout the 11th and 12th centuries Jews steadily migrated northwards. In the Ukraine the

Jewish population developed a distinct presence. In Kiev they established their own quarter -

called Zhydove - the entrance to which was called the Zhydivski Vorota (Jewish Gate). Jews

fleeing the Crusaders came to the Ukraine as well, and the first western-European Jews began

to arrive from Germany, probably in the 11th century [2].

The Kievan princes Iziaslav Mstyslavych and Sviatopolk II Iziaslavych, Prince Danylo

Romanovych of Galicia-Volhynia, and the Volhynian prince Volodymyr Vasylkovych were well

disposed to their Jewish subjects and assisted their activities in trade and finance. Jews were

also appointed to administrative and financial posts. However, as in other parts of Europe, this

benevolent treatment was not consistent.

During the Kiev Uprising in 1113 the Zhydove district was ransacked, and during the rule of

Volodymyr Monomakh, Jews were expelled from the city. The Mongol conquest of the Crimea

and of the Kievan Rus Kievan Rus strengthened commercial relations, and brought peace and

prosperity to the Jewish community up to the time of the Tatar-Lithuanian War (1396-99) [3].

It is now difficult to unpick the distinct nature of the early Jewish community in the Ukraine.

However, it was, at least partly, a Judeo-Slavic culture and had its own distinct language

(Knannic also called Canaanic, Leshon Knaan or Judeo-Slavic) and, by inference, many of it

secular customs, practices and mythology were closely linked to its Slavic homeland. Even up

to recent times there continued to be differences; with the Jewish community of Podolia and

Bessarabia speaking a sub dialect of south eastern or Ukrainian Yiddish termed ‘Podolyer

Yiddish’ and with a liturgy that owed more to a Sephardi than to an Ashkenazi tradition.

Jewish Butter Merchant 1761

During the Khmelnytsky (Chmielnicki) Uprising, many Jews sought refuge in the fortified city which

withstood attacks by the Cossacks in 1648, 1651 and 1655. Subsequently King John II Casimir of

Poland permitted Jews to reside there, and they apparently continued to live in Kamenets despite

repeated prohibitions in 1654, 1665, and 1670.

In 1672 the city was captured by Cossack Hetman Petro Doroshenko and his Turkish allies. As a

result of the treaty of Buczacz of 1672 until 1699, the town was controlled by the Ottoman Turks.

During the Ottoman rule Jewish settlement was permitted and grew to a considerable size.

In 1699, the city was given back to Poland under King Augustus II the Strong according to the

Treaty of Karlowitz.

The siege of Kamenets by the Cossack

Doroshenko and his Turkish Allies 1672

Ukrainian Jewish Children

about 1845

After Kamenets passed to Russia, Czar Paul I confirmed in 1797 the right of Jews to reside

there. At that time 24 Jews belonging to merchant guilds and 1,367 Jewish inhabitants were

registered in the tax-assessment books of the city. Two years later, in 1799, 29 merchants and

2,617 Jewish inhabitants were registered.

In 1832 the Catholic authorities in Kamenets petitioned the government to expel the Jews from

the city, basing the application on ‘ancient privileges’. The petition was rejected but in 1833 the

government restricted the right of the Jews to build shops and build or acquire new houses; in

order to prevent them from residing in the city centre itself [1]. The restriction was rescinded in

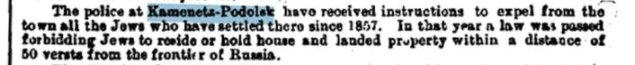

1859. However, there continued to be efforts to restrict the rights of the Jewish community and

prevent Jewish immigration into the city (see newspaper item below).

By 1847 the Jewish community numbered 4,629 and they were active in small industry, trade,

and artisanship.

Click on engraving to

enlarge

“...the issuing of such a

declaration is proof that

, despite the ban

(introduced in 1447),

Jews not only lived in

the city, but even had

their own homes and

other real estate”

[1] Kaminits-Podolsk and its Environs Randolph. Ed Abraham Rosen and others. Published by the Avotaynu Foundation Inc

Bergenfield NJ 1999. p.p.5

[2] Jewish Documents in the Kamenets Podolsk Archive by SA Borisevich and ZM Klimishina

[3] Kaminits-Podolsk and its Environs Randolph. Ed Abraham Rosen and others. From the Past by Y.Bernstein. Published by the

Avotaynu Foundation Inc Bergenfield NJ 1999.

[4] An alternative explanation is that the Kabbalistic tradition of Isaac Luria was more easily integrated into the Chasidic practice

through the adoption of Sephardi liturgy.

[5] Kaminits-Podolsk and its Environs Randolph. Ed Abraham Rosen and others. From the Past by Y.Bernstein. Published by the

Avotaynu Foundation Inc Bergenfield NJ 1999. p.p.35

[7] Jewish Virtual Encyclopaedia

[8] Kamenets Old Town by Anna Kavilsha. Published 2002

Item from News Column - London Jewish Chronicle 15 August 1886